News

UNDERSTANDING SOFT SKILLS (CNT)

By Pascal Berriot, former fighter pilot, director of studies at the Division des Vols de Salon-de-Provence, military and civilian instructor and author of several aeronautical works.

Non-Technical Skills, or NTCs, come into play when a system operator has to decide and act in the context of a dynamic activity that may present variants, hazards, constraints and risks, such as (leisure) flying or air traffic control.

"Human error cannot be eliminated, but efforts can be made to minimize, detect and mitigate errors by ensuring that people have the appropriate non-technical skills to deal with the risks and demands of their work. " [...] "Non-technical skills are the cognitive, social and personal skills that complement technical skills and contribute to safe and effective task performance." (Rhona Flin et al. / Safety at the sharp end: A guide to Non-Technical Skills - 2008).

To reflect the specific features of LAPL1and PPL training, the FFA (Fédération Française Aéronautique) has selected five CNTs (see Boite à outil FFA/Guide d'évaluation CBT à l'intention des instructeurs FFA - 2018).

- Situational awareness.

- Decision-making.

- Assertiveness and resource management.

- Workload management.

- Stress and fatigue management

SITUATIONAL AWARENESS (SA)

It is "the perception of elements of the environment in a spatial and temporal volume, the understanding of their meanings, and the projection of their states into the near future" (Endsley & Garland, 2000).

"The CS is the pilot's mental radar of the present and future situation" (JG Charrier - Mental Pilote).

"A pilot's ability to apply vigilance to the aircraft's internal and external environment. This translates into the ability to detect and identify a state or change in state of a system or the environment.

This ability underlies: awareness of aircraft systems; awareness of the environment; awareness of time" (CBT Assessment Guide for FFA Instructors - 2018).

Three levels of CS

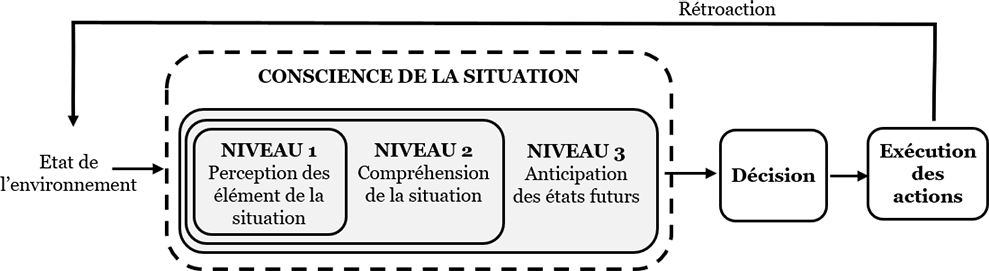

The explanatory model frequently used in aeronautics is that of Endsley (1996). He distinguishes 3 levels of CS: (1) perception, (2) comprehension and (3) projection.

- Level 1 corresponds to the perception of internal elements (in the aircraft) and external elements (the environment). Internal elements include visual information (instruments, screens, warning lights), sound (engine noise, horns, radio messages) and sensory information (stress, pressure, vibration, acceleration, etc.). In the case of external elements, this involves the perception of features such as size, color, speed, magnification, scrolling or the position of relief, runways, aircraft, clouds, horizon, etc. Erroneous perception (a sensory illusion) can be the cause of errors.

- Level 2 corresponds to the pilot's understanding of the situation at hand. Interpreting and understanding one or more elements of the situation requires a certain level of knowledge and reasoning. The construction of the representation is a process fed by two flows of information: an "ascending" flow emanating from the perception of the environment (visual circuit, radio listening, sensory feelings), and a "descending" flow directed by activated knowledge (memories, reasoning). Sometimes, knowledge of a procedure, an instruction manual, a rule or a piece of information alone is enough to understand a situation. In other cases, representation may require reference to deeper, forced reasoning (interpretations of weak signals, for example).

1 LAPL: light aircraft pilot license; PPL: private pilot license.

- Level 3 corresponds to the projection of future states of the situation. The ability to assess the consequences and future course of a situation according to its present and past evolutionary dynamics is made possible by the intellectual processing of information from levels 1 and 2. Cognitive faculties enable information to be processed more or less quickly and appropriately, leading to a decision/action.

A " strong CS " indicates that the pilot has a precise understanding of his task, integrates the various elements of the environment into a coherent picture in relation to the overall context of his mission, and is synchronized with the dynamics of the task.

A " low CS " refers to the experience of being lost, of being confronted with complexity without apparent coherence, of being behind the plane, thus out of phase with the strong external dynamics. (X. Chalandon 2013).

Figure Model of Endsley's CS.

CS, which is inseparable from decision and action, involves, for example :

- to look at the sky in the distance or read weather reports (perception) → to detect possible weather threats (interpretation-comprehension)

→ measure future risks and difficulties (future projection) → delay or cancel navigation (decision-action) ;

- hear a strange noise and observe a dubious engine parameter (perception) → suspect a probable fuel or ignition system fault (interpretation/understanding) → judge that there is a potential risk of engine failure (future projection)

→ turn around to land or divert

(decision).

Factors affecting CS

There are a number of factors that can affect situational awareness. Here are just a few of them:

- ambiguity: information from two or more

or several sources do not agree;

- Fixation or focus: concentrating on one thing to the exclusion of all else;

- lack of vigilance or attention: lack of attention is one of the causes most often cited as the cause of incidents or accidents;

- confusion: a situation that becomes increasingly complex can become so confusing that it makes it difficult to understand;

- the unexpected: an unexpected situation doesn't have to be spectacular to catch the pilot off guard;

- lack or plethora of information: flight planning and tracking applications on tablets offer a wealth of information and possibilities;

- concealed information: the pitfall of certain systems managed by automation and screen-based interfaces is the concealment of certain information. For example, the autopilot can conceal a trim sequence.

DECISION-MAKING

The first studies on cognition sought to assimilate the decision-making system to a processor that had to choose among several possible options:

"Will I have cheese or dessert? "Should I take off now, postpone, or cancel the flight? ". But the scope of decisions is actually much wider, and above all more complex and refined, than the simple choice of one option among many.

Decision-making process

The decision-making process resembles a cyclical loop comprising four important phases:

- phase 1: perception; research; and information gathering ;

- phase 2: processing of information, with analysis of the situation; logical reasoning; inventory of solutions (possible options), assessment of risks and their confrontation with know-how, procedures, available time and other imperatives;

- phase 3: choosing a solution, i.e. the

decision;

- phase 4: execution and control of the chosen option.

Factors influencing decision-making

Three main categories of factors influence the

decision-making :

- psycho-social factors: ego, the way people see us

others or the instructor, etc. ;

- cognitive factors: biases, emotions

personality, etc. ;

- contextual factors: procedures, hazards, time and cost constraints, performance requirements, passenger comfort, etc.

ASSERTIVENESS AND RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Self-affirmation

"Assertiveness is the ability to take responsibility and not let yourself be influenced. "( Aéro-Club du CE Airbus France Toulouse ACAT).

- Taking responsibility: this includes the proper application of the rules of the air, not only for oneself and one's passengers, but also and above all for other users. This implies a conscious and proactive commitment to these rules.

- Don't let yourself be influenced: there are many factors that can insidiously influence behavior, perception, analysis, reactions, choices and, ultimately, decisions. Being assertive requires a certain openness of mind to resist pressure and remain clear-headed.

There are also external factors of influence: time pressures (the time of return), pressures linked to the stakes involved in the flight (personal or financial investment, etc.), organizational influences (an order of control, habits, particular methods). And also internal factors: relational pressures, ego, entourage, moral feelings, stress, fatigue.

Resource management

"It's the ability to use available resources and to organize tasks according to these resources. "( ACAT).

The resources required for a safe flight are to be found in several dynamically interacting domains. There are three types of resources involved here:

- the pilot's intrinsic resources: these include cognitive resources such as knowledge, alertness, intuition, logic, experience, attention, etc.; and physical resources such as strength, motor coordination, flexibility, endurance, dynamism, etc. ;

- resources internal to the aircraft cockpit: documents, flight and aircraft management systems, radio, flight management aids, etc;

- and external resources: air traffic control, radio beacons, etc.

Resources can also be summed up more simply: the pilot, the aircraft, the context and the environment. The first two are referred to as "internal" resources, the other two as "external".

WORKLOAD MANAGEMENT

"Ability to clarify and define priorities, plan and organize tasks according to the situation, and manage interruptions: don't let secondary tasks interfere with essential ones. Pay attention to stress and fatigue. "(ACAT).

Workload

Pilot workload is the cost in physical and cognitive resources dedicated to performing one or more tasks. More precisely, it is the level of cognitive resources required to meet the demands of a time-constrained task (short duration or short notice).

The feeling of being overwhelmed, rushed, rushed, stressed in the accomplishment of a task depends on three parameters: the temporal deadline (duration or advance notice); the demands of the task (unfolding a procedure, monitoring a complex system, sharing attention on several things); and the investment or sharing of cognitive resources.

How do you manage your workload?

Managing workload or mental workload means dealing with one or more of the following three elements: the deadline, the demands of the task, the level of resources devoted.

- Managing time: to avoid stress or making a mistake under time pressure, you need to constantly anticipate everything that can be anticipated (medium- and long-term management). Every quiet moment should be devoted to looking at the landscape, of course, but also to preparing things that will or could happen in the next 5, 10 or 20 minutes.

-

- Reduce the demand for certain tasks: prioritize tasks according to their importance or the urgency of the situation: first fly the plane, second manage the systems. Not the other way around. Don't let secondary tasks interfere with essential tasks. Example: reprogramming a route on your tablet when the flying situation is even more demanding (on an aerodrome circuit or in poor weather conditions).

- Manage resource levels: If necessary, get help from the right seat or from the control, spare yourself from possible solicitations or distractions, avoid mental exhaustion by managing your attentional reserve, avoid mental dispersion by chatting too much with passengers, etc.

-

MANAGING FATIGUE AND STRESS

Fatigue

Fatigue can be caused by a number of factors: a lack of rest or sleep (night-time awakenings, jet lag, sleep apnea), a health problem, overwork, a psychological health problem (malaise, depression), difficulties in life, a reaction or maladjustment to the environment (professional demotivation, apprehension of a test or pressure).pressure), life difficulties, a reaction or maladjustment to the environment (professional demotivation, apprehension of a test or situation, psychological stress), etc. It's important to look into the problem in order to find the cause and implement a strategy aimed at countering the source of fatigue. This may involve simple recommendations, such as :

-

- avoid sleep debt; get enough sleep;

- eat a healthy, balanced diet, especially in the evening; avoid alcohol and coffee abuse, especially in the evening;

- be physically active;

- avoid excessive use of smartphones, especially before falling asleep.

What can you do if you feel tired?

-

- Postpone or cancel the flight: it seems obvious. The reality of certain accidents shows that it's not always easy to take your state of fatigue into account.

- During a long flight, you must try to maintain an "optimum state of mental response", avoiding too much "mental dispersion", or "cognitive sleepiness" during phases of inaction.

mental dispersion", or "cognitive sleepiness" in phases of inaction.

Stress management

"Faced with a stressful situation, the individual makes a dual assessment: on the one hand, the constraints of the situation (dangers, challenges, threats, difficulties), and on the other, his or her own resources and abilities to cope. Stress occurs when there is an imbalance between a person's perception of the constraints imposed by the environment or situation, and their perception of their own resources for coping with them. "(Lazarus and Folkman's model, 1984).

In aeronautics, "stress management" is a personal process aimed at implementing strategies to counteract both the stress factor(s) and the stress itself. The first step is to precisely identify the stressor (its origin), then to implement responses focused on the task, the situation or the situation at hand.responses focused on the task, procedure or problem resolution, rather than on negative emotions, feelings of fear or avoidance of the situation. For example, to minimize the apprehension of engine failure in the field, the procedure should be rehearsed mentally and practiced regularly. Stress can also be managed using "anti-stress tools". These tools fall into several categories:

- controlled breathing techniques and

relaxation techniques that work through the body;

- tools based on internal dialogue and concentration that work through thoughts and the mind;

- mental imagery techniques to boost motivation, performance and feelings of competence.

Sophrology is an interesting method for learning to manage stress.

SPECIFIC CAPABILITIES RELATED TO CNT

In concrete terms, a non-technical skill translates into one or more behaviors (good practices, adapted reactions), bringing into play a number of specific abilities: cognitive capacities, internal resources and human qualities. For example, good situational awareness requires the application of specific skills such as vigilance, attention, perception, analysis, comprehension, judgment, intuition, open-mindedness, anticipation, etc. These skills are developed over time, as the situation evolves. These abilities develop with each flight. Some of them are developed below.

Attention and vigilance

"Attention and vigilance" are two abilities that constitute a key internal resource for good situational awareness.

-

- Vigilance corresponds to the brain's level of alertness and its ability to process global information at a given moment. Alcohol, fatigue, certain medications and drugs alter the level of vigilance. In-flight vigilance means paying close attention to possible turns of events. It prevents possible threats and preserves you from danger. The level of vigilance depends on personal awareness and knowledge of risks, as well as a good deal of personal motivation...

- Attention corresponds to a state of concentration of mental activity on a given object (e.g. the road, the cockpit, the other aircraft in the circuit) and to the brain's ability to process information related to this object. At the cognitive level, attention enables us to take into account sensory information (visual information, sound signals, sensory sensations, etc.) and information emanating from thoughts. The brain can naturally select relevant data, but also inhibit those deemed useless: this is the selectivity of attention. At the extreme, selectivity can go so far as to induce "attentional blindness" when something in front of our eyes goes completely unnoticed, or "over-attentional blindness" when something in front of our eyes goes completely unnoticed.or "inattentional deafness", when the sound of an alarm warning of danger goes unnoticed and induces no reaction.

Sharing attention

Divided attention is the ability to perform two distinct tasks simultaneously, or to process two different types of signal. An acquired, well-automated task (e.g. cycling, walking, driving) frees up attentional resources for other tasks, making it possible to "multitask". In short, there are two cognitive circuits for performing a task: a "controlled" circuit and an "automatic" circuit. These two circuits complement each other, a little like communicating vessels: what is managed by one frees up space in the other,

and vice versa.

To manage two demanding, non-automated tasks simultaneously, you have to force the mind to alternate attention in small, repetitive sequences, a bit like zapping two TV channels to be able to watch two films at the same time. Regular (in-flight) training enables you to automate a huge number of small tasks which, when put together, free up cognitive space for other things.

The ability to judge

Judgment is the faculty of analysis that precedes the decision. It is a complex and slow cognitive process. Judging a situation involves selecting and comparing perceived information (new data) with stored information (knowledge). Several pieces of data may contradict or conflict with each other. The reflexive thinking system weighs up the pros and cons, imagining hypotheses, scenarios and possible outcomes. Of course, irrational factors (bias, emotions), pressures and influences are always present at the negotiating table. Depending on convictions, certainties, beliefs, learning, recommendations, and a whole host of other data, judgment will weigh the final decision in a certain direction. In aeronautics, a pilot's judgment is said to be "reliable" if it prioritizes safety above all else, but also certain data specific to the company (comfort, profitability, economy of means, time savings, etc.). A lack of judgment often describes a choice or decision based on emotion, impulse and/or lack of sufficient reflection.

Austerity

The weapon to combat natural tendencies to deviate from good practice is called

"rigor". Rigor is a moral commitment to respect procedures, methods, rules, directives and so on. But rigor is a fragile thing that wears out over time. Rigor can be reactivated and maintained by questioning one's own way of doing things (a flight with an instructor, a simulator session, etc.).

The ability to take initiative

This ability or human quality is a

component of "assertiveness". Initiative is the personal ability to act or initiate something on one's own, with the intention of doing the right thing. Initiative is a proactive approach aimed, for example, at saving fuel or time, improving comfort, safety or profitability, or reducing the effort or difficulty of a task. The initiative is considered "good" if the result of the intention is achieved without unnecessary risk-taking, rule-breaking or excessive contribution of internal and external resources.

Open-mindedness and mental flexibility

Open-mindedness is a quality that enables us, among other things, to overcome prejudices (preconceived opinions), habits, and harmful manifestations of the ego (scruples, pride, etc.). It is, for example, the ability to listen to advice, recommendations or remarks, while putting one's pride aside.

Flexibility or mental suppleness is the ability to conceive of several possibilities for solving the same problem. It means accepting that there are many different ways of doing things. It's also the ability to think outside or beyond norms and procedures. Flexibility means undertaking a flight or a project with the knowledge that it may have to be modified, cancelled or postponed.

The ability to reason

Conscious reasoning enables us to interpret, process, manipulate and combine real information (visual, sound, etc.) with virtual data (images, abstract thoughts, numbers, words). These thoughts can lead, for example, to a decision, an opinion or a choice. In fact, reasoning can lead to an infinite number of options. There are two main reasoning strategies.

-

- The following logical reasoning

"mental acts": logical-mathematical calculations, pragmatic and scientific approaches, correlations, logical deduction, methodical analysis, verification of information, search for coherence, reasoned criticism, objective evaluation, consideration of purely factual elements. The result of this type of reasoning is certainly reliable, but processing the information is time-consuming, constraining and very energy-intensive.

-

- Heuristic" information processing:

-

Heuristics are a shortcut used when the demands of a cognitive task are too high (time and/or complexity). Cognitive biases are part of this. So it's easier and less costly to formulate subjective judgments, beliefs, preconceptions, impressions, shortcuts, approximations, feelings, hypotheses and opinions than to resort to rational thought (cognitive economy).

REFERENCE DOCUMENTS

- Rhona Flin et al / Safety at the sharp end: A

guide to Non-Technical Skills - 2008

- Guillaume Tirtiaux / Succeeding better together /

Edipro 2019

- https://www.acat-toulouse.org/uploads/media_items/cbt-et-pilote-qualifi%C3%A9.original.pdf

- https://hal.science/hal-00824020v1/document

- https://stm.cairn.info/revue-de-neuropsychologie- 2013-2-page-69?lang=en

- Edith Perreaut-Pierre /Understanding and practicing potential optimization techniques / Interéditions

- J-G Charrier : Managing threats and errors

- https:// blog.mentalpilote. com / wp- content/ uploads/2013/10/Livret-TEM-Priv%C3%A9-5-V2- ins-article.pdf

REFERENCE WEBSITES

- https:// www. ae rov f r. com / 2023 / 01 / d e- l a - conscience-de-la-situation/

- https://blog.mentalpilote.com/2011/03/07/les-cles- de-la-performance-du-pilote/

TO FIND OUT MORE

Compétences non techniques et TEM - Explications et cas concrets par Pascal Berriot, Cépaduès edition, reference 1925, ISBN 978.2.36493.925.7, 156 pages,

2022

No comment

Log in to post comment. Log in.