News

DPSM MODELING FOR FLIGHT SIMULATION

NUMERICAL SIMULATION IN FLUID MECHANICS

Digital design tools have become indispensable. Aided by the development of computer science, numerical analysis and increased computing power, both modeling and digital simulation can be used to study, design and reproduce the behavior of complex systems. While modeling aims to represent a physical phenomenon using a set of mathematical equations to make its overall behavior more accessible and predictive, simulation focuses on the point-by-point reproduction of the visible part of the physical phenomenon. In this way, modeling gets to the heart of the phenomenon, whereas simulation only represents its effects.

In the case of flight simulators designed for pilot training, the aircraft's flight mechanics make it a complex system, and the "real-time" constraint means that numerical simulations are limited to representing the aircraft's final behavior. On the other hand, during the aircraft design phase, numerical models can be used to predict the in-flight behavior of a given geometry, a phase that requires the production of models and numerous wind tunnel measurements. Although the time required for calculations on very powerful computers may seem inordinate - we're talking weeks of computing time - the contribution made by digital wind tunnels and CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) software greatly accelerates all phases of aircraft design.

Numerous physical modeling strategies exist. What they all have in common is the resolution of the partial differential equations (PDEs) governing the physics of the phenomenon under study, but with different numerical resolution strategies. Among these techniques, the Finite Element Method (FEM) [1] is the most widespread. However, there are alternatives, such as the Boundary Element Method (BEM), which is used when the domains modeled become infinite, as is the case for external f luid mechanics.

DPSM (Distributed Point Source Method) modeling [2] is the result of work carried out in instrumentation and non-destructive testing at the SATIE laboratory (UMR 8025, CNRS/ENS Paris Saclay). Applied to model various fields of physics (ultrasonics, magnetostatics, electromagnetism), DPSM modeling has now been extended to fluid mechanics. Similar to the singular point method [3] and of the BEM type, this modeling is perfectly suited to external fluid mechanics. Non-iterative, naturally 3D and requiring only a surface mesh, this physical modeling is significantly faster than FEM for this application. Intrinsically suited to model reduction, the DPSM method enables "real-time" physical predictions, and has been successfully tested in the flight loop of a full-flight simulator [4], [5] [6].

DPSM MODELING AND FLUID MECHANICS

In very general terms, the flow of a mass fluid is described by PDEs, and in particular by the Navier-Stokes equations. The latter are non-linear and their mathematical resolution is not guaranteed. However, by introducing strong assumptions, it becomes possible to linearize them and thus obtain a satisfactory approximate solution. Assuming an incompressible, non-viscous fluid, solving the Naviers Stockes equations yields the velocity of a mass fluid in the form of two velocity field terms. The first term represents potential flows, i.e. those with an irrotational velocity field. The second, on the other hand, corresponds to flows with a purely rotational velocity field. This brings us back to a strong analogy with electromagnetism and the expression of Laplace's force, where the radial force exerted on a charged particle is due to the electric field, derived from a potential, and a rotational force due to the magnetic field.

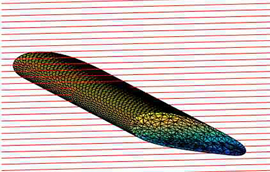

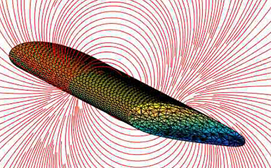

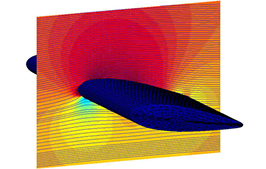

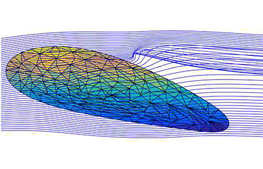

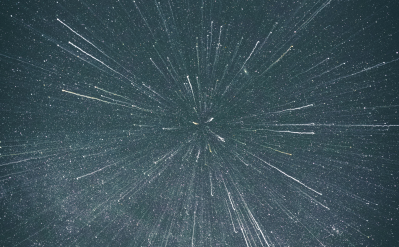

The irrotational part representing potential flows is translated in the DPSM modeling framework as a radial (or scalar) source of mass fluid. This radial fluid emission, figure 2, will oppose and/or modify the trajectory of the global mass fluid, figure 1.

Fig. 1 Mass fluid flow through a wing (NACA 4424) assumed to be transparent.

Fig. 2 : Reaction of scalar (or radial) sources when the wing is assumed to be airtight.

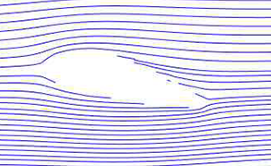

Circulation, and therefore lift, comes from the purely rotational part of the solution, figure 4. In the case of an incompressible, non-viscous mass fluid, this circulation translates into the rotation of the volume of fluid disturbed by the wing's forward motion at a given speed.

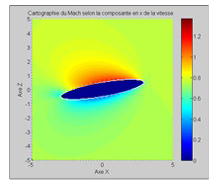

Fig. 3 Effect of radial sources on a mass flow oriented along Vx (case of a NACA 4424 wing).

Fig. 4 Circulation around the wing generated by all the rotational sources.

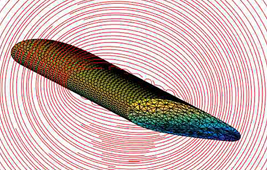

The superposition of the radial and rotational components, combined with the global wind, f igures 5 and 6, allows us to model all the phenomena to which a wing is subjected as it moves through a fluid.

Fig. 5 Effect of radial and rotational sources on a mass flow oriented along Vx (case of a NACA 4424 wing).

Fig. 6 Effect of secondary vortex sources generating starboard and port marginal vortices.

THE CHALLENGES OF FLIGHT SIMULATION

For aircraft design

With the aim of building a totally redesigned aircraft that satisfies the multiple objectives of optimum aerodynamics, minimized fuel consumption, the use of new energies and, consequently, the integration of potentially more cumbersome fuel tanks, new design tools are required. Modeling, which is at the heart of this process, must quickly and reliably predict the lift, and therefore the transport capacity, and the drag, on which consumption is directly dependent, of an object whose geometry evolves parametrically. The DPSM method is well-suited to this task, as it is non-iterative and requires only a surface mesh that can be easily modified. The reduced simulation times it requires make it an excellent kernel for calculating the aerodynamic parameters to be optimized, in the case of a p-design [7] and more generally in an AI-type scenario [12].

For flight simulators

The term "piloting" expresses both human action on a system and its control. Placed at the very heart of the feedback loop of the complex system that is the aircraft, the pilot imparts commands to the machine and measures their effects. The flight simulator (Fig. 7) must therefore be representative of the aircraft's behavior for each of its loads, including its temporal component. For this reason, these flight components are generally reproduced from tabulations extracted from recordings of the simulated aircraft's behavior during an instrumented flight. Thus, because of the real-time constraint, there is no physics in the loop, only a restitution of the behavior of an aircraft during a test flight. While this simulation of aircraft behavior may seem satisfactory during certain phases of flight, it lacks realism when the aircraft approaches the ground, typically during the simulation of take-off and landing phases [8].

Fig. 7 Fulllight flight simulator. Credit: S. Gourlaouen.

In order to reintroduce physics into the loop, particularly in terms of behavior in the vicinity of the ground, we tested a minimalist configuration of the DPSM in which the aircraft was represented by a reduced number of "hybrid" sources, a configuration known as a miniature vector model (MMV) [9] [10]. A hybrid source is one in which an elementary scalar source and a rotational source are superimposed at the same point.

During this experiment, source identification was possible because we had access to certain flight test data. When these data are not available, it is still possible to synthesize them using DPSM. Based on a surface mesh of the aircraft's envelope, the DPSM method can model and predict the forces and moments exerted on this structure during flight. It is therefore possible to estimate the value of MMV sources solely on the basis of DPSM modelling [11]. In this way, MMV simulation makes it possible to introduce a physical calculation into the control loop of a flight simulator, and potentially to reproduce aircraft behavior more faithfully in all situations.

SCOPE OF APPLICATION OF THE DPSM METHOD

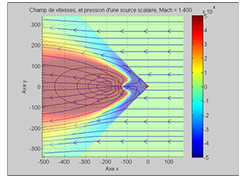

The DPSM method remains valid beyond Mach 0.3, where the compressibility term becomes non-negligible, see figures 8 and 9.

Fig. 8 - Flow at Mach 0.75. Demonstration of the MMO through acceleration of the upper air stream.

Fig. 9 - Point obstacle subjected to an air flow at Mach=1.414. Ex: Modeling of shock wave shimming by an air inlet mouse.

DPSM MODELING FOR FLIGHT SIMULATION

The speed of the DPSM method, linked to its non-iterative nature, its numerical stability and the fact that it requires only a surface mesh, mean that it can easily be considered as the computational core of a P-design or AI algorithm for the search for new aircraft structures.

References

[1] [5] Girault V. and Raviart P.-A. ; Finite Element Methods for Navier-Stokes Equations: Theory and Algorithms. Springer Publishing Company, Incorporated, 1st edition, 2011.

[2] Placko D. and Kundu T. ; DPSM for modeling engineering problems, Wiley-Interscience, 2007.

[3]Gourinat Y. ; La théorie des singularités - Un complement aux modèles locaux par éléments f inis en physique. Techniques de l'ingénieur physique chimie, Vol. Base documentaire TIP053WEB, Editions T.I., 2019.

[4] Placko D. and Barbot J.-P. and Gourlaouen S. and Rivollet A. ; Modélisation en mécanique des f luides par la méthode DPSM : applications aux simulateurs de vol. Invited conference, DGAC, Paris, France, June 2019.

[5] Placko D. and Gourlaouen S. and Rivollet A. and Barbot J.-P. ; Towards real-time aerodynamic simulations. 54 th 3AF Internationnal Inter national on Applied Aerodynamics, Paris, France, March 2019.

[6] Placko D. and Barbot J.-P. and Gourlaouen and Rivollet A.; Method for simulating a flow in which a structure is immersed. Patent EP2019071286W-2019-08-08; FR1857440A-2018 08-10. EP2015061464W-2015-05-22; FR1454675A-2014 05-23.

[7] Placko D. and Placko A. and Gourlaouen S. and Barbot J.-P. ; P-design improvement using the DPSM method. 56th 3AF International Inter-national on Applied Aerodynamics, Toulouse, France, March 2022.

[8] [9] Placko D. and Barbot J.-P. and Gourlaouen S. ; Model order reduction, application of the DPSM method to real time flight simulation. 58th 3AF Internationnal on Applied Aerodynamics, Orléans, France, March 2024. Placko D. and Gourlaouen S. and Barbot J.-P. and Rivollet A. ; New Approach of Aerodata Computation for Simulation. RAES,

Bristol, UK, July 2018.

[10] Placko D. and Gourlaouen S and and Rivollet A. ; Procédé de simulation de forces f luide. appliquées à une aile dans un écoulement de Brevet FR1750153A-2017-01-06, EP2018050214W-2018-01-04.

[11] Placko D. and Gourlaouen S and and Rivollet A. ; Device and process for measuring a physical quantity of a fluid flow. Patent [6] Placko D. and Barbot J.-P. and Gourlaouen and Rivollet A. ; Procedure for simulating a flow in which a structure is immersed. Patent EP2019071286W-2019-08-08; FR1857440A-2018 08-10. EP2015061464W-2015-05-22; FR1454675A-2014 05-23.

[12] Chambelin J.-P. and Gilliéron P. ; Au-delà du PPL, ISBN 9782383951216, Editions Cépaduès, 2024. LETTRE 3AF 2-2025 / APRIL - JUNE

No comment

Log in to post comment. Log in.